The most creative person I've ever met? Trina Schart Hyman.

The most creative person I've ever met? Trina Schart Hyman.

She was born on April 8 in 1939 and died, too soon, in 2004.

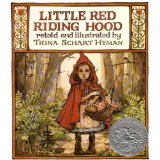

Incredibly talented as an illustrator, she was eloquent about being a creative person who loved living in a rural area. She was also kind, agreeing to meet me, then a college student, at her farmhouse in 1983 to answer my questions. She went on to win the Caldecott Medal, the highest award in children’s books, for St. George and the Dragon, and three Caldecott honors (for Little Red Riding Hood, Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins, and A Child’s Calendar). All told, she illustrated more than 150 books including some with her daughter, Katrin Tchana.

Please read on for her words about being an artist. (As the New York Times says, this interview has been condensed and edited.)

Q&A WITH TRINA SCHART HYMAN

as told to Laurie Kretchmar

On leaving New York City in 1968 after her marriage broke up and moving with her infant child to New Hampshire:

“I just had to get out of New York because it was making me crazy. I thought, either I’ll have to leave or I’ll wind up in a mental institution. I had to have a garden and I had to see space and hear quiet. It’s necessary for me to be surrounded by truth and beauty. I need it. Otherwise I can’t work. I mean I wouldn’t be able to do what I do if I worked in a factory in Detroit.”

On her early years in Lyme, NH, living with an artist friend and three children among them, and at one point having to rely mainly on the vegetable garden and credit at the Lyme Country Store to get by:

“We had no savings. We had to work real hard. A whole lot of women, especially now, ask ‘How can I get started?’ and I want to tell them that you really need fantastic motivation, like survival. If you must make your own living and support yourself and your children, if there’s no choice, then you do. You find a way or you make one.”

On work during tough times:

“If they (publishers) paid me to do it, I would do it. And in a way that was good. I think you get an added strength working on things that are not your cup of tea. It got to the point about 1972 or ’73 where I could actually start to reject some stories I knew were horrible, or not good, or not for me and now luckily at this point I can more or less call my own shots.”

Hyman worked one year in advance of the publication date. By her own estimate, she worked “pretty slowly,” spending nearly six months to illustrate a book and working on one book at a time because she said she found it difficult to keep two moods and “mind sets” at the same time.

On coming up with illustrations:

“I’m thinking about it in the back of my head, always. I carry it to bed with me, take it out to dinner and the movies with me. A lot of days it really feels like work. Some days I wish I were a waitress.”

On the discipline of working:

“I feel most at home with my work and my drawing board. If I’m depressed, if I work a little, it cheers me up. On days when I just don’t feel like working – I’d much rather be out in the garden – if I sit down and make myself work, lots of time I’ll get some really good stuff, believe it or not, so I always try and do it.”

On her vivid imagination:

“I was one of these children who probably they’d put in special education now. I was too imaginative and sensitive. I used to burst into tears at the slightest thing and I was terrified, of people especially. I had trouble, I think, separating reality and fantasy. I learned to read early and I loved to read and I just lived in storybooks and in pictures. That was more real to me than the world. And, in a way, it still is.”

On what makes a good children’s book:

“You just have to feel it. Certainly it has to relate to the human experience because children are human, too. It should have all of the things that a good adult story has only put in simpler terms so that children can grasp it.” She was partial to myths and folk tales, “because they deal with basic emotions and rules of life, good and evil, right and wrong, that still apply today. It should be something that tickles their spirit or imagination and mine, too. If it moves something in me, then I’ll do a good job on it and it will also interest children.”

On her creative process:

“I try to get inside the head of every single character.” For Snow White, “That’s a very complex, very emotionally fraught story when you think about it. Here is this beautiful woman who has a stepdaughter who is going to be more beautiful than she is. She is just driven crazy by it. She tries to kill the eight-year-old and the kid runs away and lives with seven little dwarves in the woods. How does this girl feel? She knows that that her stepmother hates her and wants to kill her and she’s completely alone. How does she feel when she sees those seven little dwarves? How do the dwarves feel when the prince comes and takes her away from them when they really loved her all these years? And how does the queen feel? To me the queen was the important character.”

“I try to get inside the head of every single character.” For Snow White, “That’s a very complex, very emotionally fraught story when you think about it. Here is this beautiful woman who has a stepdaughter who is going to be more beautiful than she is. She is just driven crazy by it. She tries to kill the eight-year-old and the kid runs away and lives with seven little dwarves in the woods. How does this girl feel? She knows that that her stepmother hates her and wants to kill her and she’s completely alone. How does she feel when she sees those seven little dwarves? How do the dwarves feel when the prince comes and takes her away from them when they really loved her all these years? And how does the queen feel? To me the queen was the important character.”

Hyman based the queen on a very good friend after getting the friend’s permission to proceed. “She’s very beautiful and striking and also very intense. I thought she’d be great for the queen. And so I tried to think of how she would react in situations. It worked like a charm. She was so upset when she saw the book– she didn’t know what a good job I’d do.”

On using friends, neighbors and family for prototypes:

“I don’t actually use them as models – I don’t set them up in costume and draw them – but I keep them in my head while doing the books.” The 80-year-old farmer across the street became the hunter in Little Red Riding Hood; her daughter became one of the sleeping courtiers in Sleeping Beauty. Hyman’s former mother-in-law was drawn into a note card, even a favorite sugar bowl once was incorporated into the border of a book’s page.

On kids believing in make-believe:

“It’s like believing in Santa Claus. Even if kids know he’s not really real in their heart of hearts, it’s nice to keep on believing as long as you can. It gives you something to hang on to. It’s a little faith.”

On her expressive artwork and elegant illustration:

“It’s in a way that I don’t think our society is anymore. It’s romantic, turn-of-the-century romantic, idealistic romantic.”

On artists who had a big influence over her — Englishmen Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac and Americans Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth:

“All had a similarity to their work: it’s romanticism that’s very dramatic, theatrical, closely allied with nature.”

On New Hampshire’s Upper Valley and trolls:

On New Hampshire’s Upper Valley and trolls:

“It’s so great to live up here because it’s full of little creatures and things. The weather is so dramatic and beautiful and the trees look like something else.”

In Self-Portrait: Trina Schart Hyman, Hyman drew pictures of Swedish trolls crouching behind rocks. She said she really does believe in trolls and fairies. “I do. I tried not to. I tried to grow up for awhile. But I didn’t really succeed. It’s a nice way to go through life. It gives things an added dimension, I guess. But it took me a long while to realize other people don’t see it that way. I sort of try and keep it quiet now.”

On research and a search for meaning, particularly with A Christmas Carol:

“I had to find out what Victorian London looked like and what people wore and what it was like. It was a terrible place and (Charles) Dickens was a great social reformer. They so exploited women and children and he knew this. He was trying to make that better with his books. I guess maybe I do too, underneath. But I’m not sure what that is. Maybe to make people more receptive and sensitive to each another and to the world. I mean, I’d like to end war. I guess I do a little feminist proselytizing because I love strong female characters.”

On strength of character and physical beauty:

“My idea of physical beauty doesn’t necessarily mean what society’s view of it is. To an artist, beauty can mean a lot of things: health, character, vitality. So if the author says a particular princess is beautiful, I know I can make her any way I want to. I can make her look like Meryl Streep or I can make her look like the woman next door who has beauty in the character of her features. It all depends. It’s just sort of temperate to the story.”

On being an illustrator:

“You have to be so motivated that you have to want to draw so badly that it’s like taking away your oxygen not to draw. It has to be so much a part of your expression and your personality that you cannot live without it. You can’t go for more than two days without drawing. I mean, it is that basic a need for me.”